Posts Tagged ‘racism’

The Freedom Maze by Delia Sherman

The Freedom Maze by Delia Sherman

Thirteen year old Sophie longs for an adventure like the ones she reads about in books. But instead, she’s stuck spending the summer of 1960 with her aunt and bedridden grandmother, in a smallish house at the edge of what was once a grand sugar plantation. So she passes time reading books and exploring the bayou, waiting for fall to come. Until the day she attempts to find her way through the once magnificent hedge maze, and finds something unexpected at the other end.

This is not a book that I can be objective about, in any way.

My maternal grandfather’s family comes from Georgia. My mother grew up in the south – the deep south – in the 1950s and 1960s. Until she turned 13 and her family moved to California, finally to stay.

In the Freedom Maze, Delia Sherman has written a story that doesn’t often get told. A story about family ties denied and forgotten – and others that are unbreakable even against the greatest of odds. About what the antebellum south was really like – and about what it means to be nostalgic for a time when owning other people was legal.

I feel like she’s telling me the story of my family that no one ever admits to.

My uncles will joke about being taught about “the War of Northern Aggression.” And my mother has rarely ever looked as sad as she did when I asked her, incredulously, if her hometown had separate water fountains when she was growing up. But it always feels like there’s so much missing. So much left unsaid.

My family would not find it flattering that I see us in these pages, but oh how I do.

It’s true that in making this story about Sophie, Sherman has centered Sophie’s point of view and growing awareness of her privilege over the the experiences and courage of her newly discovered family. Which is frustrating for obvious reasons.

And yet…

And yet I know that this is a story that needs to be told as well. My niece needs to grow up understanding what it means that her family is from the south. It’s not enough that she maybe sort of learn it once she’s an adult.

And I don’t know how to explain it to her, in large part because I don’t really have that understanding myself.

But I can give her this book.

Books 2013: Statistics

Posted on: March 28, 2014

Here is the breakdown of the massive list I posted on Monday:

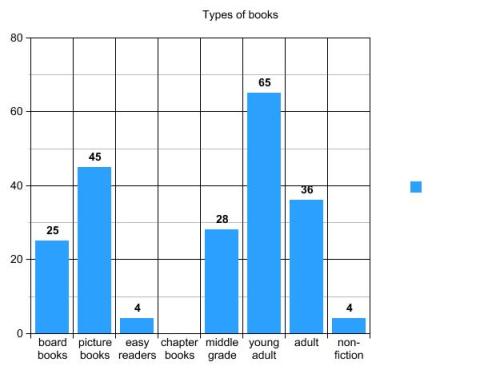

I read a total of 207 books last year.

Nearly a third (68) were young adult books, and another third were board books and picture books (25 and 45, respectively). Middle grade novels (28) and adult novels and stories (35) each made up another sixth of what I read last year. I also read a handful of easy readers and non-fiction books (4 each).

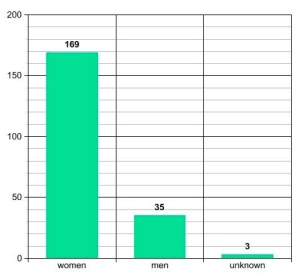

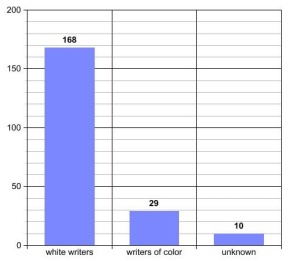

80% (169) of the books I read last year were written by women, but only 14% (29) were written by writers of color.

I’m not terribly concerned that only 20% of the books I read were written by men; there are plenty of people with much more influence than I do that seem to read and talk about only male writers, so it can’t possibly hurt for me to read and talk up female writers. In fact, it’s clearly still needed. Also, I’m probably still balancing out what I read when I was younger.

That 14% does concern me though, especially considering what I do. My reading and talking about that low a percentage of authors of color doesn’t just impact my circle of friends and what they read, it means that when I do reader’s advisory, when I create book lists and displays, and when I order books for the library, the vast majority of the books that come to mind will be by white writers. Even if I try to do searches and peruse recommended lists in order to make these all more balanced, the titles I find that way are not going to take emotional priority or stay in my head the way that the books I’ve actually read will. Which means that I’m not doing my job and that I’m failing the children I’m supposed to serve.

So my goal for this year is to double that percentage, for at least one third of the books I read this year to be by a writer of color.

I hope to eventually increase that number to an even larger percentage, to better match the demographics among children in the US. But I also know that only 10% of the children’s books published in the United States are written by an author of color, and I don’t know at what point (if ever) that reality will begin to make such goals difficult. And for this year (because of my time and budget) I wanted to start with a goal that I know is easily doable.

Open Letter to SFWA

Posted on: June 17, 2013

- In: Criticism

- 14 Comments

(If you haven’t yet, please read Amal El-Mohtar’s initial and follow-up posts for background. And also just because they’re really good.)

Dear SFWA,

SFWA members,

and fellow interested parties,

I’m not a member of SFWA. I don’t write science fiction – or any other kind of fiction.

What I am is a librarian. A youth services librarian, to be precise. Since speculative fiction is one of the most popular genres in children’s and young adult literature right now, I think it’s safe to say that my goals and yours are often in alignment.

After all, you want to get your books into the hands of readers and I want to get books into my readers hands! These may not be our only goals, of course, but as far as goals go, they rank fairly high. As a fellow professional, I appreciate all the hard work you do to make that possible. From supporting your members financially and legally to singling out their best work for praise and honors – and much more.

But we need to have a talk, because I’ve been hearing some pretty disturbing things lately.

I cannot say in strong enough words how much Beale’s actions, and SFWA silence on the matter, offends me not just as a private individual, but also as a library professional.

I don’t know if you’re aware of this, but we librarians take issues of freedom of speech very seriously. We don’t like it when ideas are silenced or people are denied access to information just because the ideas or the people in question are unpopular. We’ve even been known to do what we can to render laws unenforceable when we think they infringe upon our patrons’ right to read – or even their right to privacy (since the former depends a great deal on the latter).

Defending the public’s right to read can be trickier than it sounds at first. Librarians have learned over the years that sometimes this requires placing limits on people’s behavior while they are in the library. Solicitation, making loud noises, or being hostile to fellow patrons are all ways in which private individuals can infringe upon others’ right to free speech within the library. All of these, harassment especially, disrupts people’s ability to make their own reading choices in privacy and without fear. It’s not just a matter of fighting back chaos, it’s about respecting everyone. Not just the people who are the loudest or most demanding.

The SFWA is not a library, nor is it a workplace. But it is supposed to be a professional venue. The same basic concepts about free speech and workplace harassment apply.

US law says that Beale has every right to whatever opinions he has on any subject. He has every right to express them – in his own space, on his own time. I’m certainly not going to advocate for libraries start filtering access to his site. I wouldn’t even be opposed, assuming space and budget and collection development policies indicate it would be a good choice, for his opinions to be neatly shelved alongside all our other books, where patrons may choose to read or ignore them as they wish. It can hardly be more inflammatory than Mein Kampf or less scientific than the latest book by Glenn Beck.

But the moment that Beale used SFWA resources to promote his opinions is the moment that he made his speech more than just about him and his own rights and his own opinions. He’s made it about you – all of you – about your integrity, about your professionalism, and about your good judgement.

This is the part that worries me.

As a librarian, I like being able to look over the titles of the Norton award winners and nominees. It has been one of the many resources I can go to for suggestions on what to buy or recommend to my teenaged patrons, and it’s been a very interesting and helpful one.

But recent events, and your silence about them, threatens the integrity of this resource.

Beale may have his own opinions about the the capabilities of “a society of NK Jemisins” but I have professional obligations to my young patrons. Obligations which includes fostering their hopes and building up their skills and resources, even for those patrons Beale would deride as “savages.” When I choose books for my library’s shelves, for library programs and displays, I choose them based not only on literary merit, but also on what they offer my patrons in terms of interest, personal growth, and joy. When I go to various resources for suggestions and advice, as the sheer volume of books requires that I often do, I’m making a choice to trust the judgement of others. This includes trusting them – trusting you – to, unlike Beale, see all my patrons as worthy of respect.

You can see my dilemma now. For the problem now is not just that Beale is one of your own, but that he has appropriated your voice. In blatant disregard of your own policies yes, but unless there are appropriate repercussions for such actions, there must be doubt about your commitment to your own policies. Doubt about your our own integrity.

What does that say about your judgement? The judgement I have until now relied upon?

Perhaps it doesn’t matter to you, individual SFWA member, if I continue to pay attention to the Norton nominees and winner each year, or if I don’t. It matters to me, though. When I say that I use the list of Norton nominees as a resource, I say this as a librarian and a reader who has passion for the genre and experience evaluating it.

And when I say that the Norton Award will mean nothing to me, going forward, without Beale’s expulsion, I say this as a librarian who knows my own library’s collection well. I know that what is most missing from my library’s collection are stories by and about the very people Beale has insulted and dehumanized. We already have Tolkien and Heinlein. We will continue to purchase Cory Doctorow and Neil Gaiman’s latest whether they are nominated for the Norton or not. What I need are reminders to make room in the budget for stories like Akata Witch, Above, Hereville, and Ash. Books that tell my most marginalized and oft forgotten patrons that they, too, belong in the library. That they, too, belong to a world of stories and worlds of possibilities.

But how can I trust you to help me with that when you can’t even manage to treat your own members with respect? What is your judgement worth, if it fails to understand the difference between private speech and blatant disregard for organizational policy and goals? What am I saying to my own patrons if I trust the judgement of people who associate with men who refer to them as “savages”? If I trust the integrity of people who make excuses for shocking displays of racism?

If you lack the most basic respect for your own members, if you lack the most basic belief in the humanity of the patrons I serve – of the youth I serve – then I have no use for you.

Sincerely,

Jenny Kristine Thurman